|

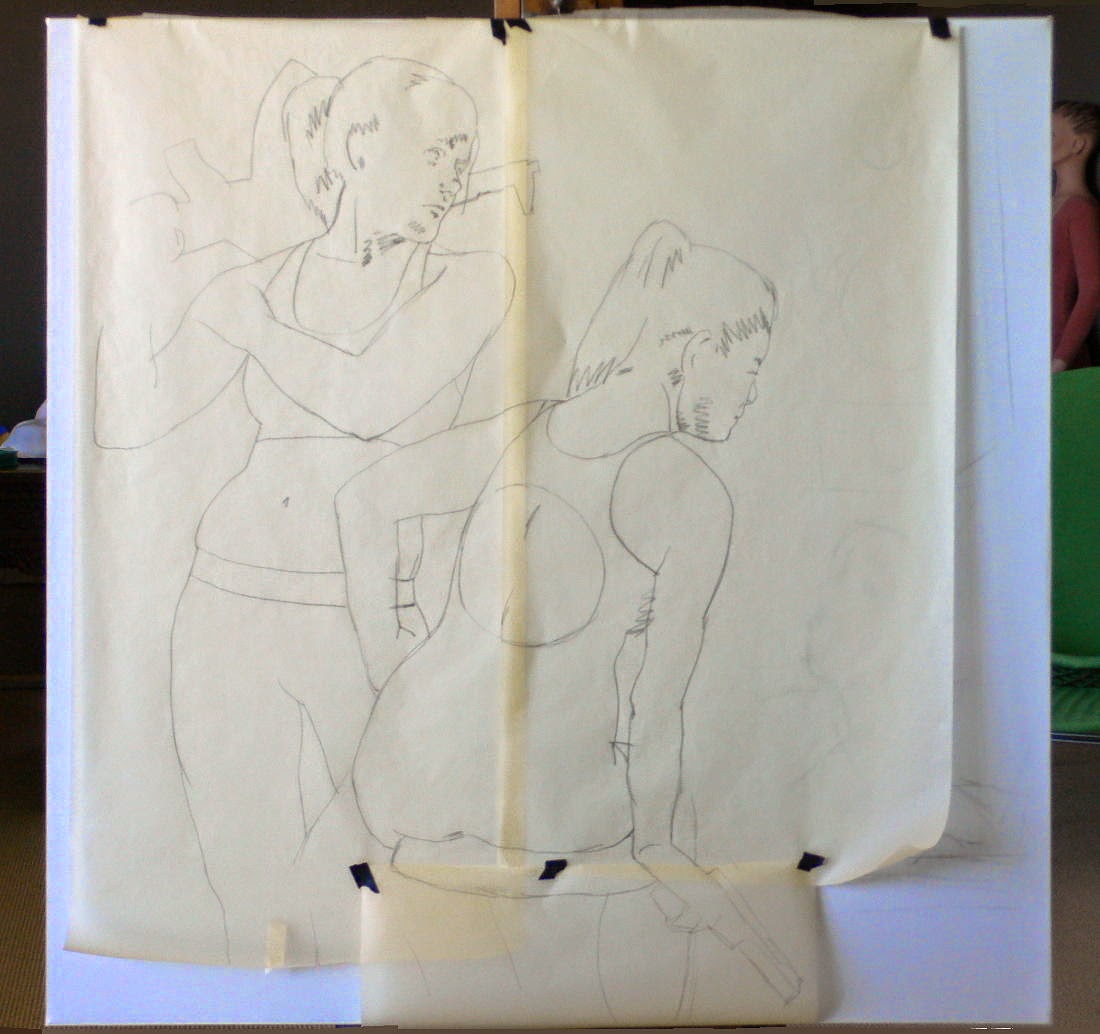

| Helen's drawing of F. |

|

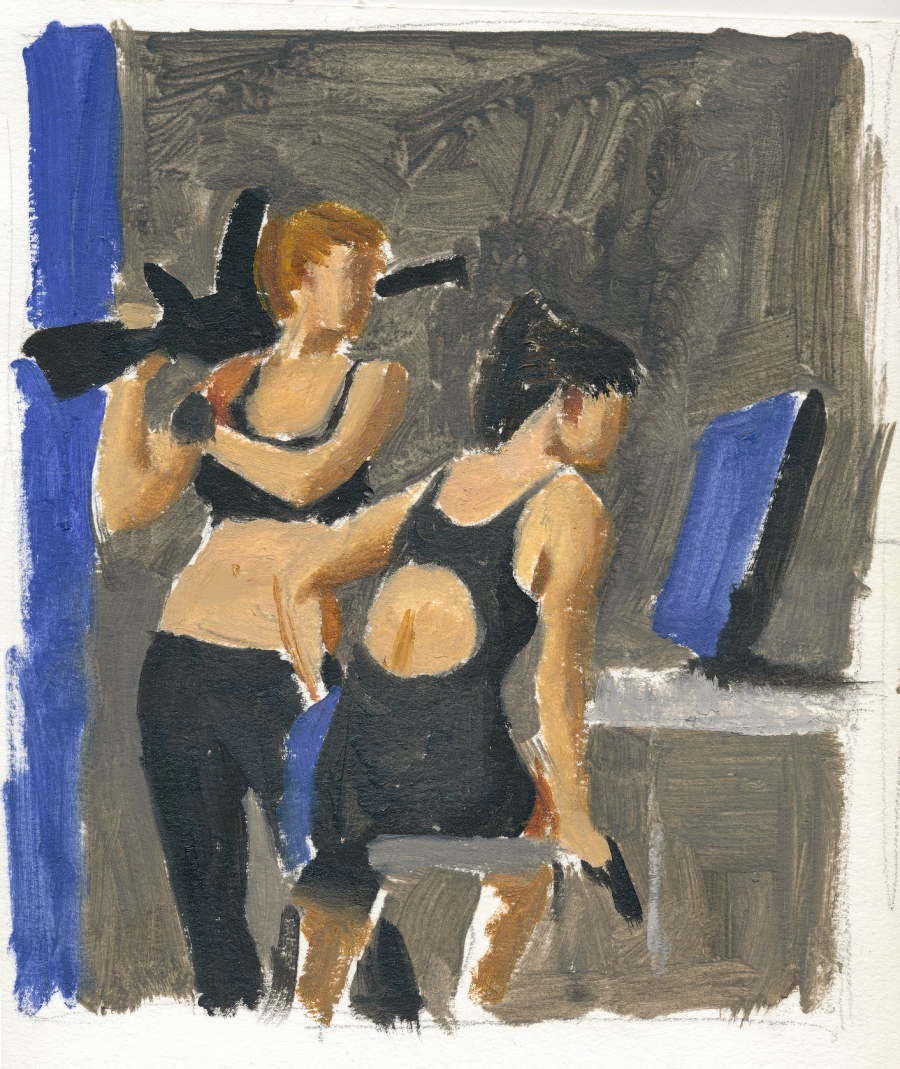

| Andy's oil sketch of F. |

Helen learned the process of making life masks from a talented colleague here in Chicago. Helen made the life mask using plaster-infused gauze, available commercially. First she had F. cover her face thoroughly with vaseline, then cut the plaster gauze into strips of varying sizes, which were soaked in water before being applied to the model's face.

Once the whole mask hardened (the plaster tends to warm slightly as it sets) the mask is carefully pried off the model's face. This negative mold is left to completely dry. To make a positive, powdered plaster and water are mixed to a paste, which is then poured into the negative mold and left for many hours, until the compound is hard and cool to the touch. At that point the mold is removed and discarded. The results can range from good to incredibly detailed, with every pore and lash showing.

The photos show something of the process described above. I suggest the model remain upright in order to create natural looking cast. If you would like to try it, check out the many YouTube videos on this topic.

This leads us to recall a debate among representational artists, well-documented in the Renaissance, about the 'truth' of capturing nature in 3D vs 2D. As painters, we were trained in the many ways to depict the what we saw on canvas, including scale, perspective, effects of light and atmosphere on the recognition of space, not to mention figure anatomy, color theory and paint application techniques that connect to creating effects of form, weight and volume. Of course, while sculptures learn many of these essentials, they rely on other concepts and techniques not necessarily used by painters.

In this 15th century debate, known as the Paragone, painters and sculptors in Italy competed to prove the superiority of their respective media, at conveying the reality of nature, for want of a better term. We can't say which of these two is better; perhaps neither is a great as architecture or drawing (which Vasari claimed), but we do know that Helen and I find that the tactile process of cast-making and pouring plaster to create a life-size model helps us imagine the texture and weight of the human head when working from photo references.